CW: Mentions of death and blood

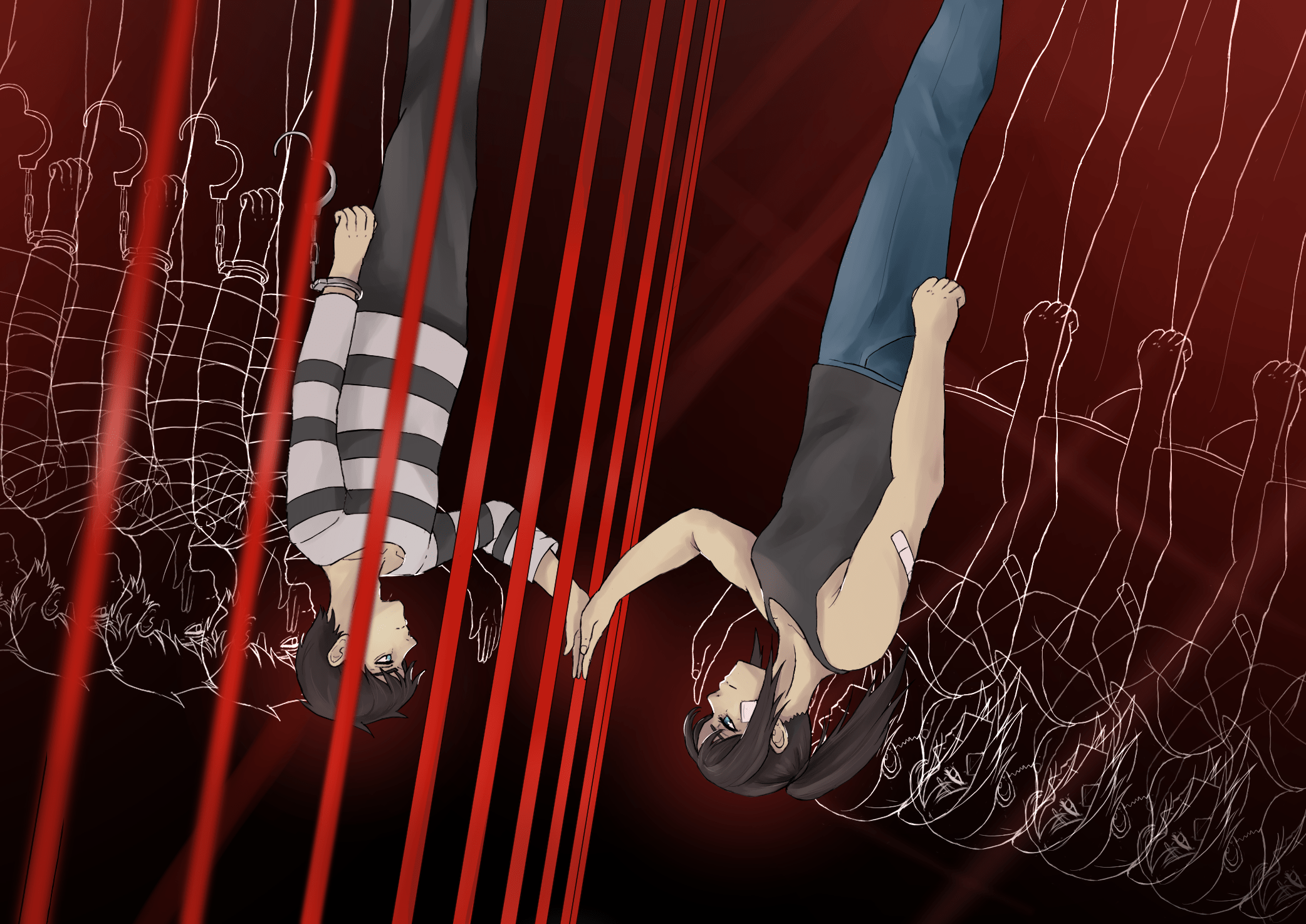

Between the poor and the rich, there stood metal bars. They were cold, frosty bars, with ice embedded in their very core, and blood-stained from all the good people who tried to climb or take them down.

They were the same bars that separated Freya from her brother.

They all knew he did nothing wrong, but the prime minister’s daughter had run to her daddy about some sort of imagined slight, and now Rance was in jail.

Their parents had cried. It was Rance — the last person they’d have expected to have a blemish on his perfect record. He wasn’t like Freya, who came home every day with scuffed knees and bruises on her face, having won another fight. Freya, who talked with her fists and loved with her knuckles, who was raised in blood and rust. No, Rance wasn’t like Freya.

Rance was a genius.

He was the one who channelled running water into their home, when the closest well was five kilometres away. He was the one who stayed up until midnight experimenting with electricity, not stopping until everyone in their village had free light and he had burn marks on his forearms. He was the pride, the light, the hope of the family. But now he was behind bars.

With luck, he’ll be out in 20 years or so, and have to rebuild everything from scratch. Without luck, he’ll be in there for the rest of his life. After all, society was harsh towards poor convicts, wrongly-blamed or not.

Don’t cry, Freya reminded herself. She never cried. And she wasn’t about to now, waiting for their turn to visit Rance; even if they were family, they didn’t get first priority, and were stuck sitting on hard plastic chairs for what seemed like hours.

“A shame that such a pretty face is stuck in jail.” They could hear the Prime Minister’s daughter cooing in a sickly sweet tone. She was the one talking to Rance now, eager to boast, her face twisted with glee. “If only you hadn’t refused. Couldn’t even give me one little kiss?”

Freya clenched her hands into fists, but Rance said nothing, staring at the wall.

The minister’s daughter continued gloating.

Freya put a hand on her Ma’s, who was gripping her bag-strap so tightly her knuckles were turning white. Beside her, Pa had his hands on his knees, forcefully open and still. They wore identical expressions of politeness, so blank and stiff that Freya could almost see how angry they were. But even if all three of them were sitting there, fuming with barely contained anger, they could do nothing.

The bars between the rich and the poor were too high. Too cold. Too frosty.

“Oi! I’m talking to you!” The girl said to Rance now. “Look at me.”

Rance did as he was told. He looked tired, with dirt-crusted hair, his mouth pressed into a hard line, shoulders drooping. But his blue eyes were the same, burning bright.

“What a shame.” She purred again. “You could’ve been the next prime minister.”

Rance called her a word that made both her parents reach for Freya’s ears, but she brushed them away impatiently, tired of being treated like a child.

“Careful.” The minister’s daughter’s eyes glittered, hard and unforgiving, like the gemstones on her necklace. Just that one gemstone could probably buy Freya’s entire village. “Wouldn’t want something to happen to… your sister, was it?”

All the fight left Rance’s eyes.

He apologised.

Finally, after what seemed like eternity, the girl’s visit was over, and she pushed past the family of three with an air of satisfaction.

Freya had never wanted to punch someone so badly before.

But Rance was waiting, so she rushed in instead, crushing him in a hug.

“Hey.” He said, sounding exhausted and relieved at the same time. “You smell like cinnamon. Have you been making bread with Ma again?” His voice was raspy, gritty, like the badly-lain gravel path in front of their house, but Freya had never heard anything better.

“Yes.” Their Ma sounded like she was on the verge of tears again. Ever since the news came that Rance was found guilty, it’s been waterworks non-stop. “She has. She’s been so helpful.”

Their Pa clapped Rance on the back, hard, like he had done when Rance had come home with the school science competition trophy, holding 50 dollars in his hand. Rance had given it to their parents, but Freya knew Pa had secretly been holding onto it, along with weekly savings from his job, placing it all inside a shoebox labelled ‘Rance’s university’. That shoebox was still under their bed, a testimony to a crushed dream.

“Sorry, guys.” Rance offered them a smile. It was his smile, crooked, with a dimple on one side. “I’m sorry.”

Ma was crying now, tears leaking out of her eyes silently. “Stupid boy. Don’t say that.”

Even Pa’s eyes were watery. “Not your fault, sonny. It’s gonna be fine. You’re gonna be fine.”

Freya was still holding onto Rance, eyes as dry as ever, gripping onto the back of his shirt with a vengeance. A vengeance she would still be clinging onto when it was time to leave, screaming at the guards who tried to take Rance away, kicking and fighting, clawing at whoever was closest, because she knew, through some sort of premonition, that this meeting can’t end.

That was the last time she ever saw Rance.

Visiting fees were expensive, and if you didn’t pay extra, the prison guards would find all sorts of ways to send you away again. Prison life was hard, and for Rance, who was always a skinny stick who liked messing around with his gadgets in the kitchen rather than going out to play soccer with his friends, prison life was fatal.

He died of a respiratory disease, alone.

Freya didn’t even get to say goodbye.

It was a rainy day when she first visited his grave. Rance’s favourite. It’s nice when it’s stormy, he had said, you get reminded that the sky isn’t just a pretty painting in the air; it has so much power, and you remember the strong winds and the loud thunder long after it’s gone. Freya could hear him, as if he was right next to her, his voice reassuring and strong, looking up at the gathering clouds. She fell to her knees.

How could he be gone?

She knelt there long after everyone else had left, waiting to hear his voice again, to see him wearing faded blue jeans with rips in the knees, to squish her cheeks and tug her hair and come up with some wacky idea for a new bicycle addition.

But he couldn’t.

There are bars between the poor and the rich. Bars that were dripping in red, all the blood of the innocent people who died for the petty privileges and pleasures of the rich and the spoilt. Rance’s blood was just one drop of many.

As Freya’s knees sank into the wet dirt, she finally felt the first drops of water on her cheeks. The tears ran with the rain and suddenly she couldn’t stop, sobbing with abandon, the pain hitting her all too quickly in the chest, leaving her gasping for breath. Through blurry vision, Freya made herself a promise. A promise on Rance’s grave.

She will make them pay.

Written by Amy Zuo and edited by Kevin Xing. Published on 30/7/2023. Header image by Bruze Zuo.